Last week, President Trump announced that the United States and India had agreed a trade deal. Whilst the deal is not expected to be signed until March, Trump claimed that India had committed to stopping imports of Russian oil. For the tanker markets, such a move would be significant and lead to further adjustments in oil trade flows. However, India faces a number of challenges in weaning itself off Russian oil, whilst Russia itself will struggle to redirect Indian volumes to alternative markets. Notably, the Indian government is yet to acknowledge the agreement to cease Russian oil imports entirely.

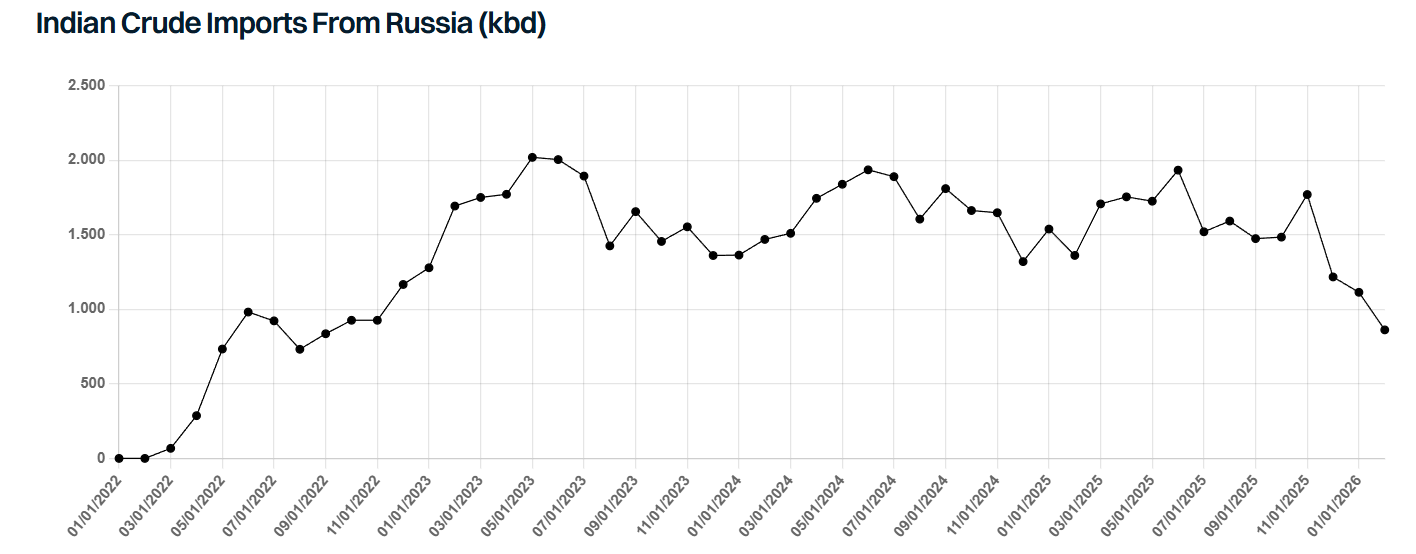

India has already made significant cutbacks in Russian crude imports, receiving 1.1mbd in January, down 46% from average 2025 levels as sanctions and US pressure have reduced purchases. Imports were already set to temporarily fall further as Rosneft’s Nayara refinery enters maintenance in April. However, in the short-term flows might actually increase, with several refiners having recently returned to the Russian market following steeper discounts and replacement suppliers for the now sanctioned Rosneft and Lukoil. Looking ahead, it seems inevitable that imports will ease further on political pressure.

The key questions then become, where does India replace from and where does Russia redirect to? In terms of alternative supply, Trump’s recent announcement suggested India would take more from the US. However, light US grades such as WTI are not a direct replacement for Urals. Indian refiners would likely prefer to take more Middle Eastern, Latin American, Venezuelan and perhaps even Canadian barrels over WTI. Interestingly, a blend of Venezuelan Merey with WTI could be a viable substitution and suit America’s policy objectives. However, this would likely prove less economic than Middle Eastern grades. For displaced Russian crude and products, China is the only viable large-scale alternative, though some Middle Eastern countries may take more Russian fuel oil as power generation demand rises. Given the loss of Venezuelan supply and risks to Iranian deliveries, China likely has capacity to absorb additional volumes. However, this all depends on independent refiners obtaining favourable pricing, sufficient import quotas, as well as having the required risk appetite. Higher Russian flows into China also risk backing out mainstream barrels, potentially putting downwards pressure on benchmark freight rates.

Russia will also likely face growing logistical constraints with its oil on the water reaching record levels last month. Longer journey times and difficulties selling have also raised costs and increased dark fleet demand. If Russia struggles with a shortage of tonnage, it may eventually be forced to cut production or further expand its shadow fleet.

In the near term it seems certain that India will further reduce Russian imports in favour of mainstream cargoes, leading to another shift in demand from the dark to mainstream tanker fleet, likely increasing upside volatility in freight rates. Yet Russian oil will not simply disappear, making China’s appetite for these cargoes a key factor for the strength of the broader tanker market. Let’s not forget, the harder it becomes to sell Russian oil, the steeper the discounts on offer, the more tempting those barrels become and perhaps, the more pressure on Russia to find a path to peace.

Data source: Gibson Shipbrokers