Following two weeks of unrest, the oil market is again focused on Iran after a period of relative calm since last summer’s 12‑day war. At the time of writing, the government appears to have quelled much of the unrest. Even so, the threat of potential US strikes, deep public dissatisfaction, disruption to Black Sea exports, and ongoing developments in Venezuela have kept the oil and shipping markets on edge. It remains difficult to predict the outcomes in the event of a US attack, a major escalation of protests, or regime change.

In the near term, the biggest risk is an attack against Iran. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps has stressed that any attack would trigger widespread retaliation across the region. The primary threats remain disruptions to flows through the Strait of Hormuz and attacks on regional oil infrastructure, whilst a strike could also prompt the Houthis to resume Red Sea attacks on shipping. In such a scenario, insurance premiums and freight costs would likely rise to reflect higher regional risk.

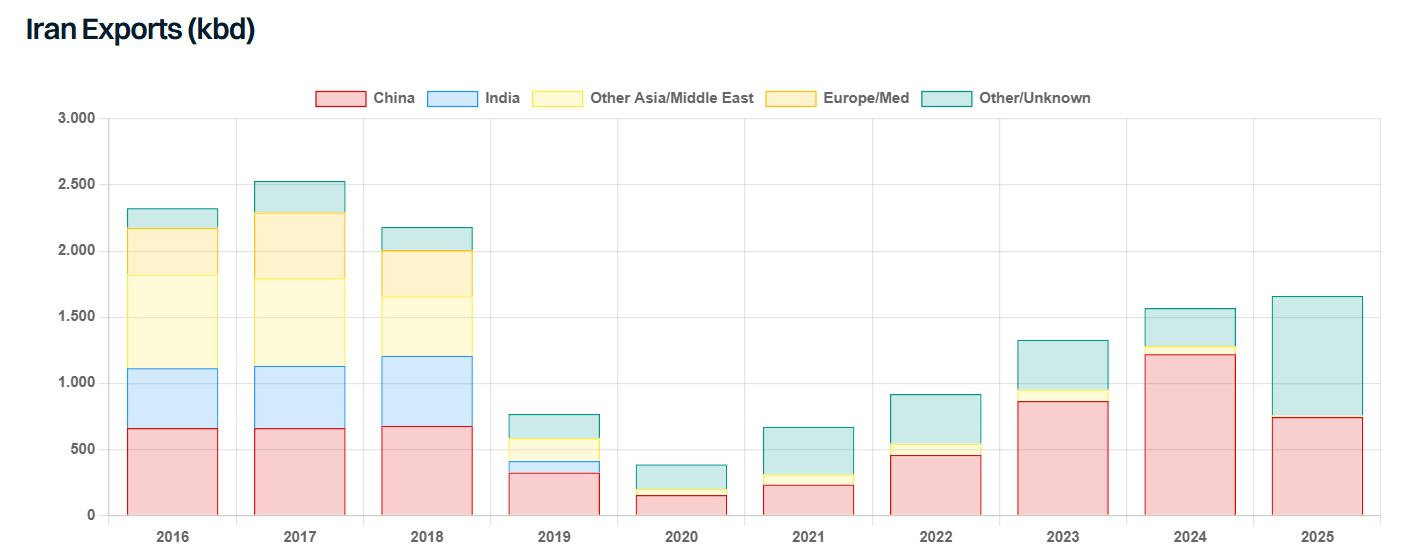

It is also impossible to ignore the risk that a regime change might have major implications for oil production. Despite intensifying sanctions pressure, Iran remains a major oil supplier. According to FGE, last year the country pushed total oil output to 5.18 mbd (3.64 mb/d crude, 0.80 mb/d condensate and 0.73 mb/d NGLs) – the highest level seen since the 1970s. As with Venezuelan barrels, Chinese independent refiners are most exposed to any disruption, with almost all Iranian crude exports supplied to China. If Venezuelan and Iranian availability tightens further, these refiners would be forced to seek alternatives, likely boosting demand for Russian and mainstream crudes.

Conversely, a regime change or rapprochement with Washington could lead to a normalisation of Iranian exports. Whilst it could take years for such a scenario to materialise, the impact on tanker markets could be profound. At the peak of sanctions relief in 2017, Iran exported over 2.5mbd of crude to international markets, compared to an estimated 1.5mbd last year, mostly to China. In the event of sanctions relief, Iranian crude is likely to quickly return to India, Europe and the Mediterranean, as well as South Korea and other major Asian economies. Whilst Iran has plenty of ships at its disposal, most of these ships would not meet the vetting standards of mainstream buyers, prompting a shift back to conventional tonnage. Gibson estimates under a modest scenario of 2mbd of exports, sanctions relief against Iran would generate demand for 25 VLCCs and 20 Suezmaxes, assuming trading patterns similar to 2018.

At present, the Islamic Republic is the second-largest user of dark tonnage overall, with roughly 20% of the dark fleet engaged in Iranian trades. For VLCCs however, it is the largest dark fleet player. Of the approximately 200 dark VLCCs, almost all are supporting either Iranian or Venezuelan exports. Taking account of recent developments in Venezuela, rapprochement with Iran could finally lead to the largescale removal of these ships from the global oil supply chain to the benefit of the compliant tanker market.

Events in Iran therefore have the potential to lead to a seismic shift in tanker markets, however, only time will tell whether the status quo is maintained, or the US continues to ramp up the pressure on the Islamic Republic. Yet, with geopolitics rapidly shifting and the US shifting tactics from tariffs and sanctions to military means, all bets are off as to how the situation evolves over the course of 2026.

Data source: Gibson Shipbrokers