The three things investors should know as we enter a turbulent 2026

Iran and Venezuela are capturing the spotlight, but overall they have less of an immediate effect on the global economy and investment portfolios.

Inflationary (trade wars) and disinflationary forces (weak labour market), are powerful on both sides, so no outcome is certain.

Businesses should worry about the geopolitics in terms of their supply chains. But portfolio managers should look more into the possible effects of a subjugated Fed.

----------------------------

Summary

In terms of geopolitics (Venezuela, Iran), it has been one of the most interesting weeks in memory. However, the immediate effect on the global economy is very little. If oil shortages occur due to disruption, OPEC+, who have chosen a low-price strategy, can compensate. For the time being, we project stable oil prices, unless OPEC+ changes its stance. For more oil to come online and change pricing dynamics altogether, years could pass. Ultimately, oil matters so much as an offset to tariff-related inflation. But inflation is significantly affected by other factors as well, and most importantly, a very weak jobs market in the US. Geopolitics matter to businesses, to be sure. A world carved into spheres of influence could significantly hamper global supply chains. For portfolios, the Department of Justice’s latest endeavour to harass the Fed could be more consequential over the longer term, but over the short term, an uber-dovish central bank could even improve returns for some assets.

--------------------------

“I’m worried about Iran”, I texted our CIO, Ben Seager-Scott, a few nights ago. ”Especially what it could do to the price of oil.”

2025 was a year of near-record geoeconomic and geopolitical upsets. 2026 seems eager to snatch that crown from the very first days. Within a matter of two weeks, we are seeing regime change in Iran and Venezuela. Two events decades in the making, potentially happening within days of each other. A geopolitical cosmogony.

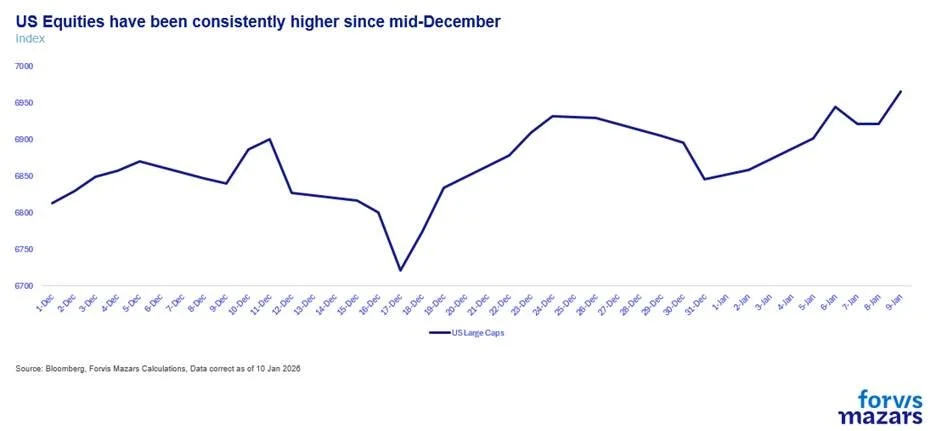

Yet, markets seem unfazed by these events. Are our portfolios oblivious to rising risks as the world becomes evidently more unstable? Stocks have been going up since the back end of 2025

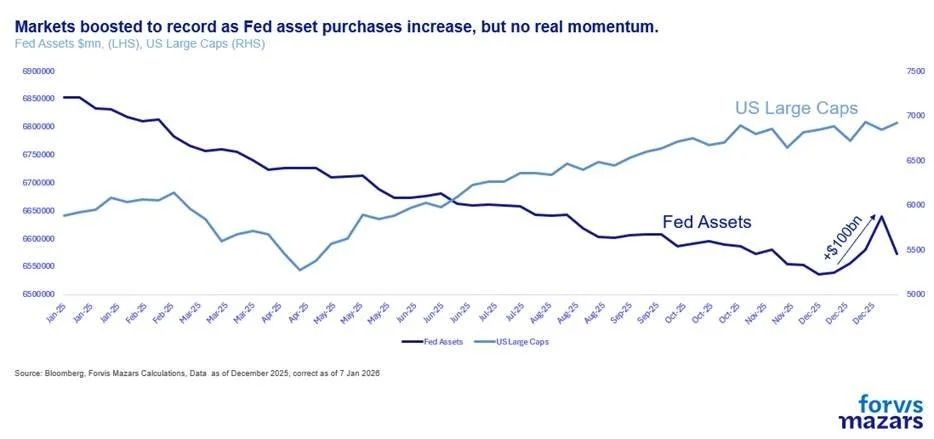

while the US Federal Reserve is once again buying securities in the open market, to make sure that market turbulence, as it stabilises its reserves, remains well managed (to be sure, this is risk management, not Quantitative Easing, as reserves may drop as well as rise).

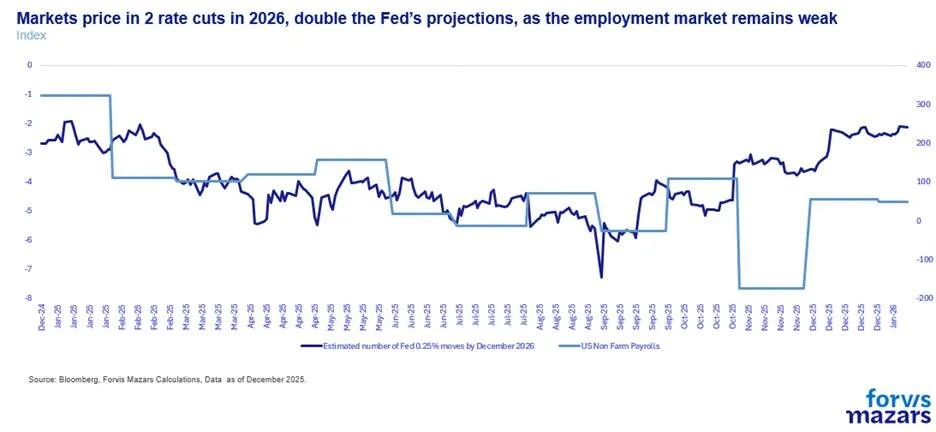

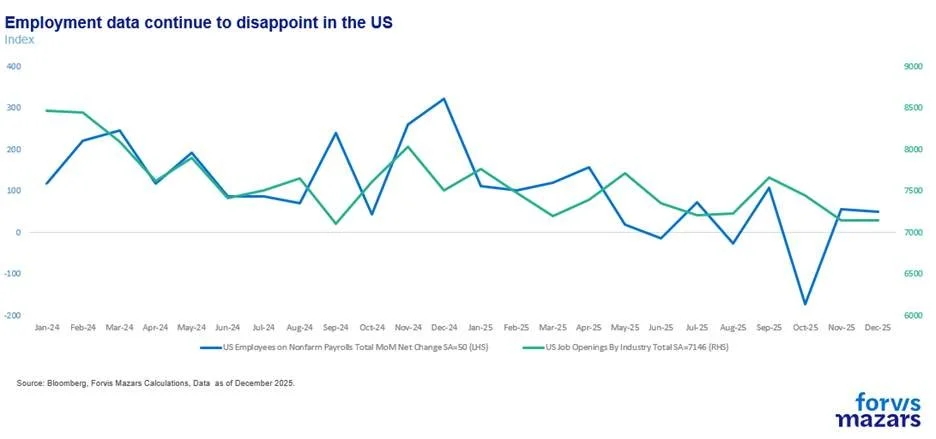

A weak employment market suggests that the Fed will also continue to cut rates in 2026, possibly more than once, as it has previously suggested.

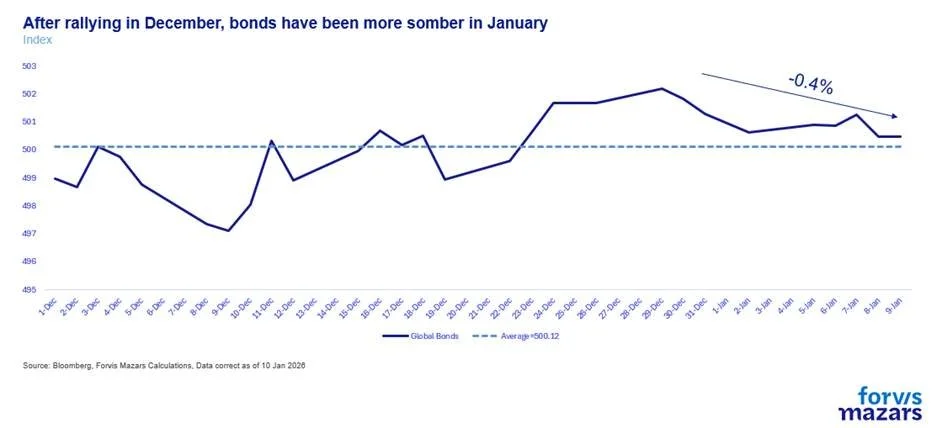

The equity market is, probably for the right reasons, more optimistic about the potential for AI adoption in 2026, than it is worried about consequences from geopolitics. The bond market, the place to gauge such risks, is slightly more negative, but not emitting an SOS just yet.

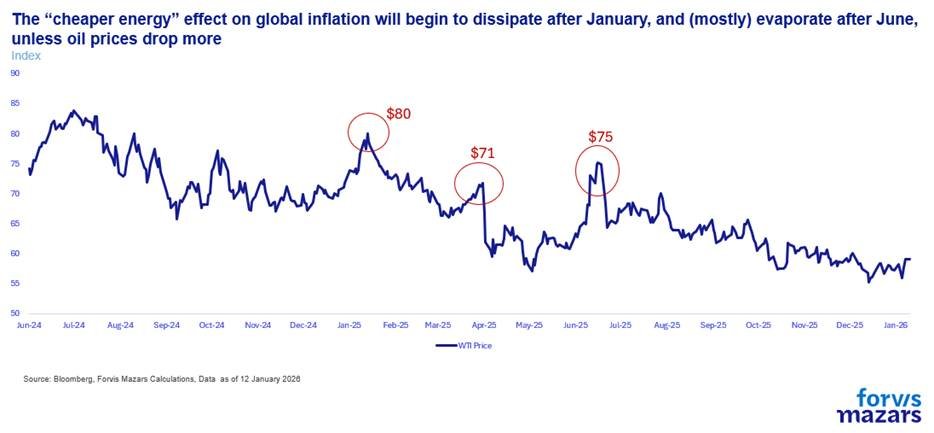

Still, my economic brain can’t relax. Last year’s trade war should have wrought much worse outcomes for the global economy than it did. The variable that changed the equation was a 25% drop in oil prices, courtesy of Saudi Arabia who found its way back into America’s good graces. Lower inflation, coupled with AI investment, helped keep real growth above projections. Yet the oil disinflation boon begins to run out after this January, and could significantly dissipate after June, unless oil drops below $55.

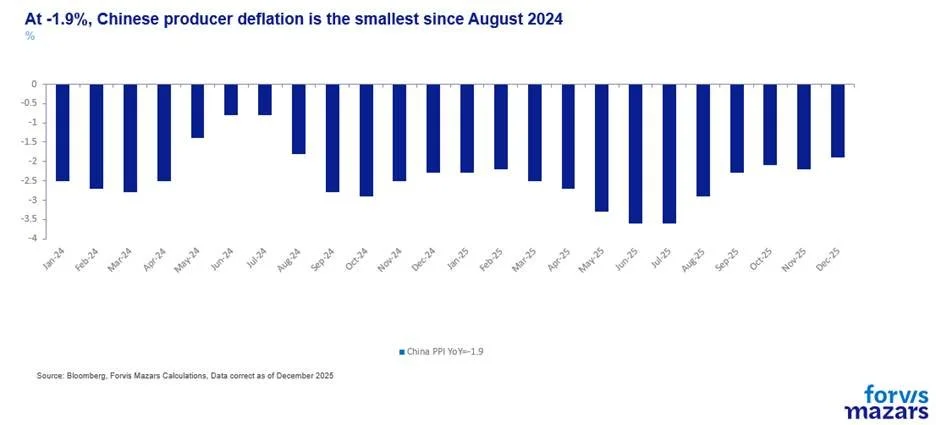

Adding to inflation worries is China, which is seeing a resurgence in inflation. Producer prices are still negative year-on-year, but they have been rising in the past few months.

Companies may also want to increase the amount of tariffs they pass on to their customers, as their pre-tariff inventories run out. Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs and other investment firms have said that their thesis for 2026 is that prices will increase as consumers will be called upon to pay more than 37% of the cost of tariffs, which they did in 2025.

Of course, to be clear, there remains one big disinflationary force: lower employment in the United States. Despite the Trade War, we feel that a jobless boom will likely not be an inflationary boom.

And disruptions due to protests in Iran and instability in Venezuela could, in the short term, cause some turbulence in oil prices. But that’s hardly a long-term argument for higher oil prices. In Iran, either protests die down, and oil production returns to normal, or they succeed, and a new regime rises, which will likely need more oil revenue to stabilise itself. Venezuela knows, under any regime, that after years of economic hardship, a way needs to be found for the economy to enjoy healthy profits from oil. At any rate, oil will eventually flow, which seems to be Washington’s singular goal, in its pursuit of a manufacturing renaissance and a win in the battle for AI dominance.

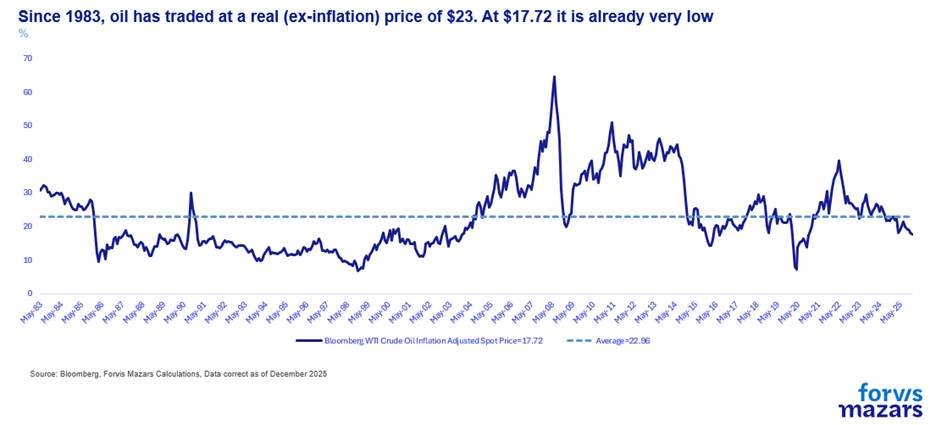

While more oil flowing eventually from Venezuela and possibly Iran is good news, OPEC+ could still regulate the flow of the bulk of oil to make sure prices don’t drop much further than this. Stripping for inflation, oil has been trading around $22 /barrel since the 1970s. It is now trading at $17.7. Going lower, which is the only way it could further disinflate the world after June, could become troublesome for oil economies, including Texas’s.

“How would that work” Ben wondered, returning to our original point. How would all this disruption really hurt oil prices? Higher producer inflation out of China can be balanced against possibly a higher output from Venezuela, or Saudi Arabia regulating prices to remain close to their present levels. Short-term disruptions can be dealt with. The possible regime change in two countries hostile to the global economic order is actually the best geopolitical news in years.

So this is our point.

It’s easy to worry about geopolitics. But, if anything, 2025 should teach us that things could play out badly, as much as they could play out well by the end of 2026. Washington's campaign to acquire Greenland, in a bid to wean itself from China’s stranglehold on rare earths, could spell the end of NATO, or it could pressure Denmark into a profitable deal with the US. And while Russia and China could use Venezuela as a way to win more moral high ground in their bid to corner Ukraine and Taiwan, the truth of the matter is that the moral high ground in a “Realpolitik” transactional world is less important, and that independence of both those countries lies with the exact actor that disrupted Venezuela: the US Government.

Similarly, it’s easy to worry about the White House subjugating the Fed, stoking up inflation and causing a melt-up in long-term yields. On Sunday 11 January, the Fed Chair Jerome Powell said that the central bank had been handed subpoenas over from the Department of Justice over the cost of its renovations. He said: “The threat of criminal charges is a consequence of the Federal Reserve setting interest rates based on our best assessment of what will serve the public, rather than following the preferences of the President.” At the time of writing, large-cap futures and the Dollar were down and gold was up, as the first reaction was a “risk off”. Portfolios tend to react to the Fed, much more than they do to geopolitics.

Nevertheless, let’s remember that inflation doesn’t primarily come from the Fed. It is aided by its potential unwillingness to constrict the economy enough to fight it, but it is not a primary source. Low energy prices and weak employment conditions could keep prices in check for a while longer (and certainly until April, by which time we will see lower inflation as a result of the year-on-year effect in oil prices). Similarly, it’s good to remember that even a subjugated central bank can be good for markets over the short and medium term. A compliant Fed could succeed in affecting long-term yields if it buys long-term bonds from the market, even if eventually inflation spirals higher.

What does this all mean for businesses?

The message in 2026 is the same as in 2025. There’s no reason to be overly pessimistic. The global economy, despite all obstacles, is, for the moment, humming well. Inflation can be affected by many factors, not just interest rates and tariffs. Central banks, independent or not, can absorb short-term pressures before they turn into crises. Similarly, one should not mistake a lack of pessimism with the abandonment of caution. A world with distinct spheres of influence can be very damaging for the global supply chain. Electronics, cars and other complex items that are used by most consumers and also to run most businesses globally, could face shortages, or at the very least become a lot more expensive.

What does it mean for investors?

We don’t know how things will play out in 2026. But a portfolio isn’t about clairvoyance. It’s about balancing the optimism that capitalism will deliver over the longer term, against the proper pricing of short and long-term worries.

The Fed’s independence is very important, to be sure. But I will become the heretic and say that central bank independence may not be the only reason inflation was kept in check in the past fourty years. I can also say that, while we all look at potential long-term risks, portfolio managers are evaluated on an annual, rather than a 10-year basis. While over the long term, a less-than-independent Fed is probably bad for inflation and long yields, over the short and medium term, investors could still rely on its dovishness to deliver good outcomes for equity and bond markets (lower short rates, improved financing conditions). Investors should not ignore the possible short-term boost to focus on the likely long-term repercussions. Taking advantage of an uber-dovish Fed utlising the asset classes most likely to benefit (high-duration bonds not being one of them), could build a portfolio outperformance necessary to balance out potentially harder times ahead.