William of Ockham was a 14th-century English Franciscan friar. As an unusually clever person, he wasn’t very much liked by either the church (for insisting on inserting logic into theological discussions) or by the Pope himself (presumably for being English on top of being a smarty-pants). He is best known for Okham’s “razor”, a philosophical theorem. “Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem”, which translates as "Entities must not be multiplied beyond necessity", or simply put “the simplest explanation is usually the best one”.

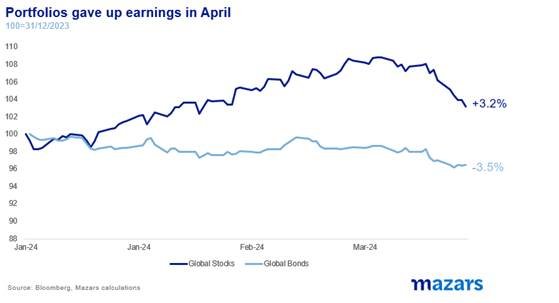

Okham’s razor will come in handy, as we try to interpret the rout in risk assets during the last three weeks. Both bonds and equities have been losing ground since early April, during an episode which was reminiscent of the QE era, when assets were more correlated.

Global stocks, which have been consistently rallying since the end of October and gaining as much as 26%, are finally correcting, by about 5% from their highs. Global bonds are also down 2.2% in April and 3.5% for the year. The Dollar, a global safety asset, is rallying, gaining 2% against Pound Sterling and 1.2% against the Euro in April alone.

There have been a number of narratives that may explain this move, however no particular one seems to fit the bill.

Let’s explore them one by one.

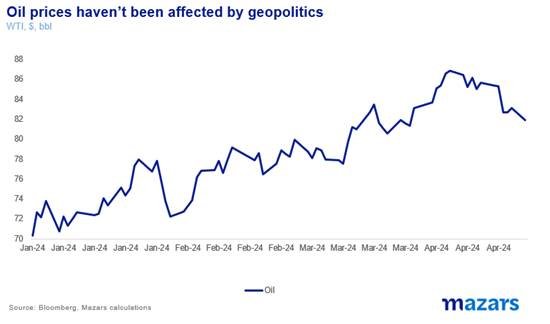

1. It’s not the geopolitics. While things in the Middle East have certainly been heating up, we have not seen a major escalation of hostilities in the past week. More importantly, the price of oil has remained relatively stable, and certainly well below levels which could conceivably cause a third inflation wave.

2. It’s not the Fed: The primary culprit could be the Fed keeping rates “higher for longer”. After a series of strong US inflation and employment data, Fed officials came out en masse in the last couple of weeks and more or less confirmed that we should not expect many rate cuts this year, if any. Michelle Bowman, a board member and a hawk, even wondered whether the Fed had under-tightened, or a rate hike is warranted. Former Treasury Secretary and perennial Fed Chair candidate Larry Summers has raised the possibility of rate hikes as well.

However, the argument doesn’t stand up to serious scrutiny. The simple fact remains that the S&P 500 is 2.5% higher it was in mid-January, when bond markets were pricing in 7x cuts. Throughout the period, equity markets ignored sticky inflation and bond markets repricing less rate cuts and just kept going. There’s no particular catalyst that we see which could conceivably just make equity investors more rate-aware.

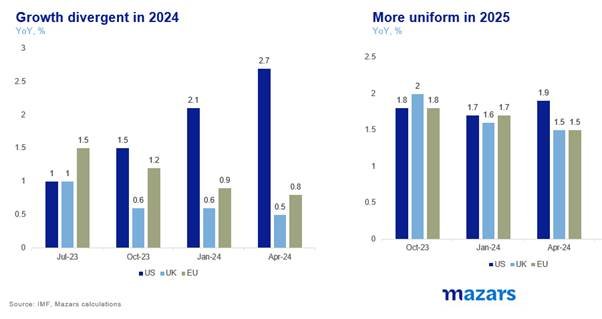

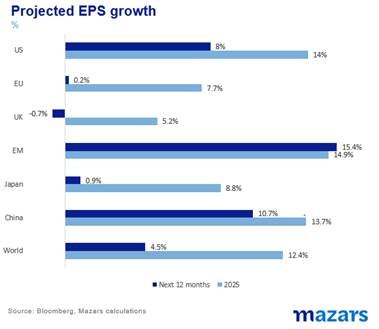

3. It’s not growth: Economic growth lifts earnings growth, in theory at least. Just last week, the IMF published its bi-annual World Economic Outlook, in which it raised 2024 global growth prospects from 3.1% to 3.2%, with the US significantly upgraded from 2.1% to 2.7% by year’s end. While Europe and the UK were slightly downgraded (0.8% and 0.5% growth respectively, 0.1% below January’s estimates), their outlooks haven’t worsened significantly.

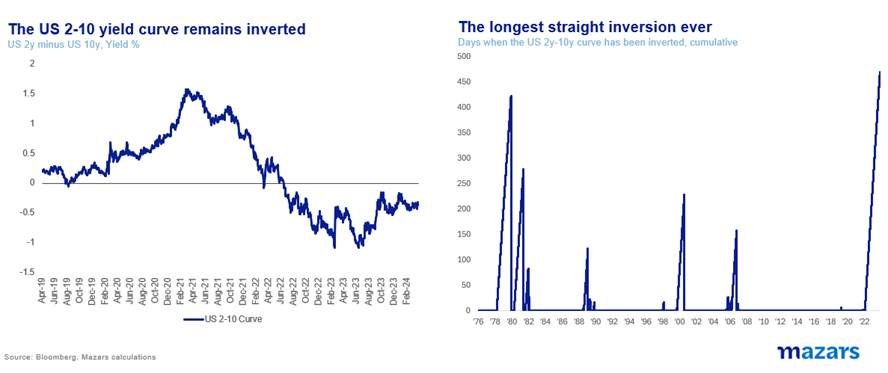

Despite key indicators flashing red, the developed world hasn’t experienced a recession. The US 2y-10y yield curve has remained inverted for 470 straight days, by far surpassing the previous record of 423 days in 1980. It is also the deepest inversion in the last 50 years, reaching 1%. Even the present number, 0.4%, by comparison, milder, represents the trough in many previous episodes. The fact that we don’t have a recession is a reflection of two issues. One is that the central bank may have actually under-tightened, or, simpler, the US which has been fiscally expanding, has spent the money wisely enough to spur growth. At any rate, growth concerns are possibly not behind the latest equity setback.

4. It’s not earnings. According to Factset, of the 14% of S&P 500 companies which have so far announced earnings, 74% have beat net income expectations. Arguably, a smaller, 58% beat for top-line earnings and a 0.5% is nothing to write home about, but certainly not the catalyst to cause a correction.

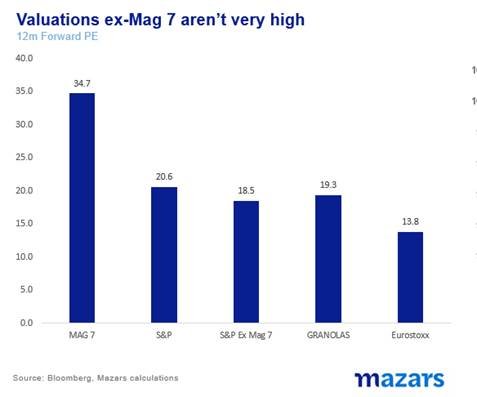

5. It’s not valuations. This might come as a surprise, but equities were not that expensive in early April. Yes, US equities were trading at a 19% premium over their long-term average at the time, but a 21.5x forward price-to-earnings is hardly “irrational exuberance”. Meanwhile, the rest of the world, including Europe, was trading at a discount. The 496 S&P 500 companies that are not the Magnificent 7 (the S&P 500 currently has 503 members), are trading at 18.5x forward earnings, very near to the S&P 500 long-term average.

Having exhausted both events and fundamentals (Monetary policy, Growth, Earnings, Valuations) we can now turn to technical reasons. After all, the market has been dominated by algorithmic trading in the past few years.

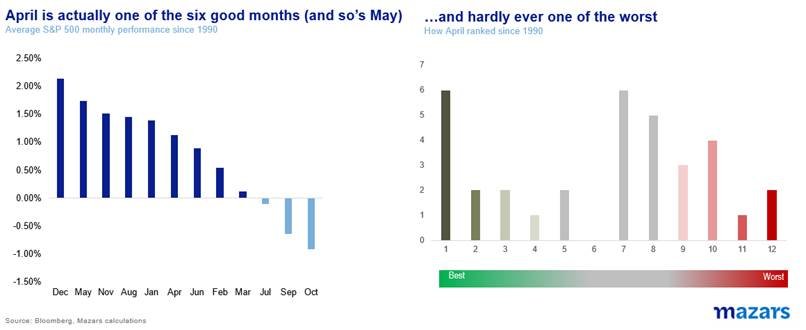

6. It’s -probably- not the ‘algos’. Algorithms tend to follow patterns. And while they would enhance a move (say a 2% drop becoming a 5% drop or a 10% rally becoming a 20% rally) they would need something to instigate a move large enough to follow. Lacking a specific catalyst, they would usually turn to seasonal trends. Yet, here again we hit a roadblock. April is not usually a bad month for equities. And May (when old traders advised to “sell and go away” is actually one of the best months in the year). I do have some reservations about this call, to be sure. Any one black box is mysterious enough, so a market of black boxes is pure enigma. And while we can’t see any clear trend emerging, we can’t help but notice that the last three major moves happened exactly at month’s end (a drop after end July 2023, a rally after end October 2023 and now again a drop after end March 2024)

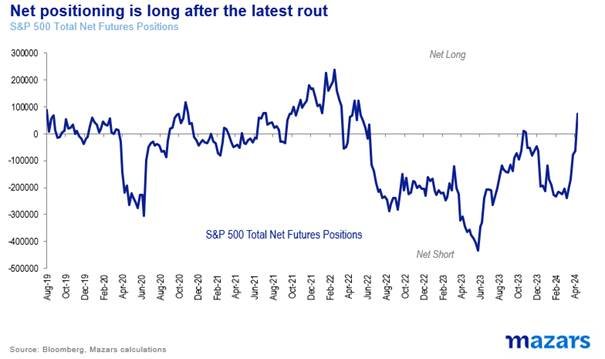

7. It’s not the futures market. Up until a few weeks ago, while leverage was unusually high, net positioning for the S&P 500 was a significant short. In the past few days, positions have moved to exactly neutral. A short-squeeze is usually beneficial for pricies, and by no means explains a downward movement.

8. It’s not the debt. A point of concern from the IMF’s latest report was that the US had issued too much debt, which is not sustainable and may risk unbalancing global growth. In a separate report, they also said that concentration in the bond market, 50% of the US 2y Treasuries futures markets are held by fewer than eight traders. It makes sense, especially after years of central bank buying which has crowded out many bond trading desks, that the market is thin. Combined, these two pieces of information could spell trouble for the bond market. However, the nature of bond risks is non-linear. Markets tend to react violently after a specific event, say a default but do not linearly price in rising risk. As for the debt levels? Equity markets have long learned to live with it, especially if it comes from the world’s biggest economy which also holds the global reserve currency.

So the simplest explanation is that, lacking a major catalyst, nothing has changed in the past few months. Despite the recent action, equity and bond markets are looking at different things. Bonds are slowly and painfully climbing back from the absurd position at year end that the Fed would cut 7x times. It has yet to price in any rate hikes. Our base case position remains that the US central bank will begin cutting at some point later in the year.

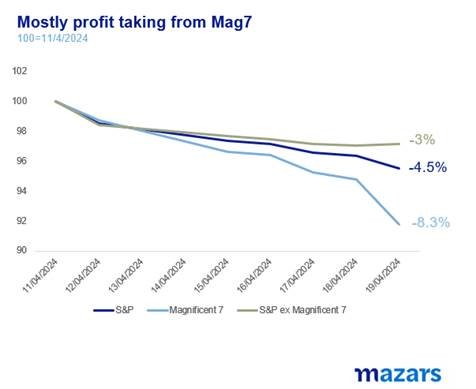

As for equities? A simple look at the graph, tells a story of the Mag 7 leading the fall. Lacking a clear catalyst, we should assume that it is mostly profit-taking from positions that have rallied significantly over the past few months. Mean reversal is part and parcel of regular investing life.

Should investors be concerned? For the time being, they are not. A net long position in the S&P 500 futures markets, suggests that traders are buying the dip.

The rally may not have had strong legs, but, seemingly, neither does this correction.