‘…when you see one cockroach, there’s probably more’

Jamie Dimon, CEO, JP Morgan

Fears over potential credit losses in US peripheral banks causing a systemic credit event have somewhat subsided. Investors and businesses, however, are still somewhat worried.

Losses appear to be small relative to the banks’ balance sheets.

If the problem persists, like in 2023, bigger lenders or the central bank have a lot of firepower to step in.

--------------------------------------------------------

Summary

Recent loan fraud disclosures at U.S. regional banks and bankruptcies in the auto sector have revived memories of 2008-style stress. While losses remain contained and no deposit flight has emerged, tightening credit conditions could expose hidden vulnerabilities—especially in opaque private equity and leveraged lending. Still, systemic buffers are strong: major U.S. banks hold about $200 billion in excess capital, and the Fed stands ready to ease policy. Financial fragility persists beneath a bullish market, but history suggests swift central bank action remains the ultimate safety net, tempering systemic risk even amid rising credit concerns. So maybe the better entomological question is not whether ‘cockroaches fly solo’, but whether ‘the insecticide is strong enough’.

--------------------------------------------------------

Late last week, equity markets retrenched as some US peripheral banks (Zions and Western Alliance) disclosed suspected loan fraud. This comes on the heels of the collapse of First Brands (a US auto part maker) and Tricolor (an auto financing company), a few weeks ago, as well as a 20% three-month selloff for the Blackstone Secured Lending fund. Markets recovered a day after, mostly on positive sentiment after good earnings from US large caps, but also due to a general equity-bullish sentiment permeating Wall Street in the last few weeks.

Yet, simmering underneath are worries about financial stress.

The signs to anyone having a job previous to 2008 are familiar: Failing lenders and questions as to where the risk lies. Jamie Dimon, JPMorgan’s CEO, implied that credit risks don’t come in isolation. Failed companies usually cause stress to their borrowers, and the stress tends to ripple across the market. This has been the experience of every major financial crisis recorded. Risk asset rallies masking fragile financial conditions are indeed a dangerous cocktail.

It becomes even more dangerous considering that Private Equities are involved. It’s no coincidence that the Bank of England has been reportedly considering stress testing private credit (although we can’t help but wonder what the mechanism might look like). The Private Equity market, which flourished in the decade-and-a-half of ultra-cheap financing, is facing harder conditions after interest rates began to rise. Regulators were happy to let them take on a much bigger role post-2008. If they failed, the thinking went, it would not be as bad as the Great Recession, since they weren’t systemic. The problem with PE is two-fold, of course: a) Their transparency requirements are much lower than banks, which means their losses remain undisclosed. b) They are still not independent from the financial system, as they borrow heavily from banks to finance their purchases.

So banks do have risks. And these risks may be compounded by their own Sword of Damocles, unrealised losses after the bond repricing which took place after 2022. ‘Unrealised’ can become ‘realised’ if a bank is forced to sell assets, in case, for example, depositors increase withdrawals. The liquidity challenge remains for banks, especially peripherals. Unrealised losses are not a ticking time bomb, but they can become a serious issue in times of real stress. Still, it would be good to remember that by March (for when the latest data is available), these were about 40% below peak.

What banks don’t have yet, is evidence of a serious credit risk buildup. These come from bankruptcies.

There are several mitigating factors:

First: banks with failed loans are holding up.

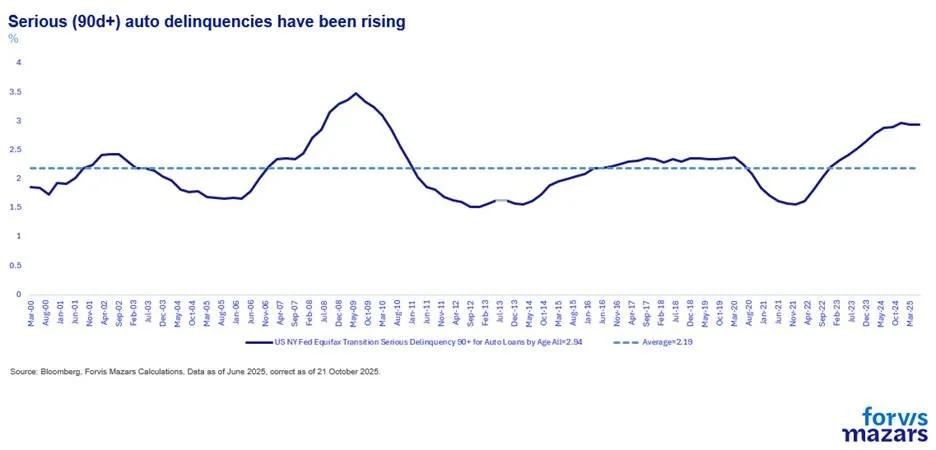

The credit losses from First Brands and Tricolor are close to each other, and they do reflect a bad auto loan market, a known risk.

But the fact that the bad debtors belong in the same market suggests that the problem is not yet widespread. Both banks rushed to ease investors' minds, reiterated their outlooks. Zions $50m charge is low compared to its balance sheet of $88bn, 0.06% of total assets. Fifth Third Bank, another entity which had $200m at risk in Tricolor, has a balance sheet of $210bn. Both banks will likely recover something.

And at the time of writing, no deposit flight was observed. In fact, Zions, Fifth Third and Western Alliance recovered most of their losses on Monday.

Still, investors may rightly be worried about stresses appearing in other areas. If banks begin to reduce credit (despite rate cuts) it could become an issue. The latest US Small Business Survey showed a sharp reduction in credit availability perception.

Which brings us to our Second point. Systemic balancers and tailwinds. In the 2023 peripheral banking crisis, larger banks stepped in to alleviate the pressure. JP Morgan estimates that the top 13 US banks have $200bn in excess capital. And considering a wide push for deregulation, the number could rise significantly, easing the pressure for both the core and the peripheral banking systems.

The central bank, which is now in easing mode, can also readily step in. In 2023, the Fed expanded its balance sheet by $300bn, even as it was raising interest rates. This time around, markets are pricing in two cuts until the end of the year.

What this means for businesses and investors

This piece, in many forms, has been written countless times by myself and thousands of other analysts: “don’t fear, the problem isn’t too big”. Enron had a nearly-universal “buy” rating right before its collapse. This one is a nice reminder, too:

So no, we will not utter the most poisoned words in the history of finance, “This Time is Different”. Risks are risks, and they could very well accentuate, which is why we continue to monitor this (and every other risky) situation closely. The lesson from history is that there might very well be more “cockroaches” that we would not discover until it's too late. Parochially focusing on one company or sector misses the probability of systemic events.

Having said that, financial systemic events have a financial systemic cure: the central banks’ promise to act quickly as a stabilising force. Over the last 17 years, we have seen that central banks have learned that it’s better to fire the monetary “bazooka” early rather than late. While the Central Bank Put may, at some point, prove ineffective, for the time being, we are confident that financial markets will find it more difficult to panic, knowing that the monetary safety net will be there for them.

So maybe the better entomological question is not whether cockroaches fly solo, but whether the insecticide is strong enough.