Remarkably, global crude steel output in 2023 was flat year-on-year (1,888.2m tonnes), with China virtually unchanged (+0.1% to 1,019.1m tonnes).

Flat overall growth conceals massive variations in individual countries’ performance.

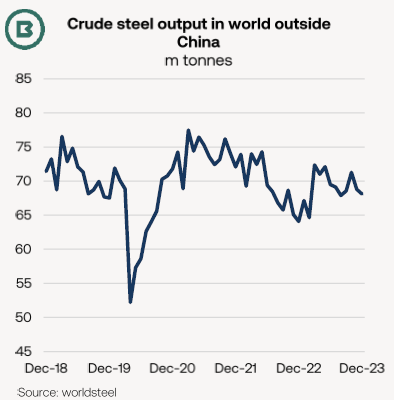

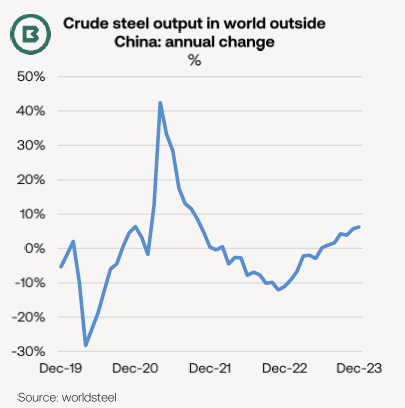

The two charts below both show crude steel production outside China—the first tracks tonnes produced, the second annual change—which begs the question: are we seeing stagnation or recovery?

After the rebound from the collapse of April 2020, a pattern of declining monthly peaks emerges through the course of 2021-23.

Last year’s monthly high for the world excluding China, for example, was 7% short of the peak month in 2021.

The other conspicuous feature of the first chart is the softness towards the end of 2022. This is what shapes the upturn in the second chart, lending the appearance of an early-stage recovery through the course of 2023. In the 2H 2022, post-lockdown lows were recorded in Europe, Japan, North America and South Korea.

As a result, this may disguise some underlying weaknesses. Closer examination of national data shows that upward trends in production were scarce in the last months of 2023, with one very notable exception—India.

According to initial estimates from the Joint Plan Committee of the Ministry of Steel, India’s steel consumption jumped 14% last year (to 132m tonnes).

At the same time steel exports from India retreated 16% to 6.7m tonnes, whereas the country’s imports gained 28% to 7.2m tonnes, a symptom of rising demand.

Perhaps one of the downside risks for the country’s steelmakers could be competition from China across Asian export markets.

We anticipate further expansion in India this year, even if the rapid growth of 2023 is not matched.

What then are the prospects for other leading steel producers this year?

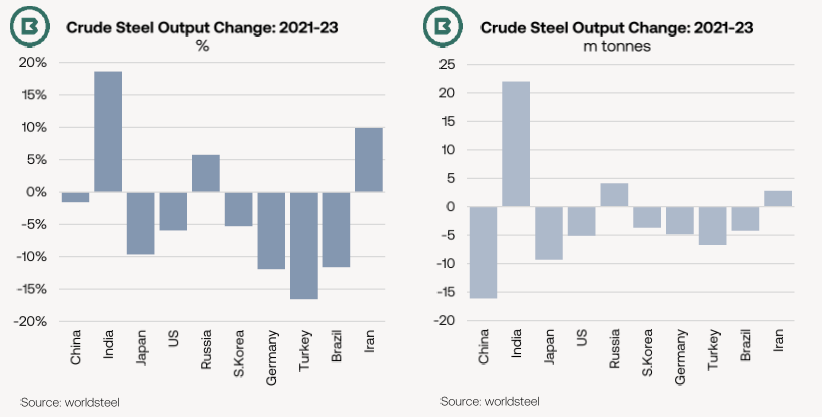

The charts below demonstrate the two-year change in crude steel output between 2021 and 2023 in absolute and percentage terms by the world’s ten largest producers.

Aside from India, the only two countries to experience growth were Russia and Iran.

Significantly, from the point of view of steelmaking raw material imports, steel in Japan, South Korea, Germany and Turkey reduced by almost 25m tonnes combined over the two years.

As China drove iron ore import demand in 2023, can the rest of the world contribute more this year?

In Europe, blast furnace restarts (from Belgium and Germany to the Czech Republic and Romania) will spur iron ore and coking coal demand.

The charts below demonstrate it would not require a return to 2021 steel output levels for coking coal and import demand growth in Europe, Japan and South Korea to be generated in 2024. A partial upturn would suffice.

China

Finally, China’s December data point was important in a longer-term context: thanks to a -15% year-on-year dive, for the first time since 2021, the Chinese monthly total slipped below 50% of the global figure.

While we are certainly not glossing over signs of softness in China’s steel sector, December’s total resulted in annual production in 2023 being held at the 2022 level.

This reminds us of the reports from China-based media groups, such as Caixin, back in April, which suggested the country’s authorities planned to limit 2023 output at 2022 levels. Part of the aim was to “limit oversupply”.

Maybe conveniently, December’s monthly total has ensured that flat growth was achieved in 2023 as a whole.