By Ulf Bergman

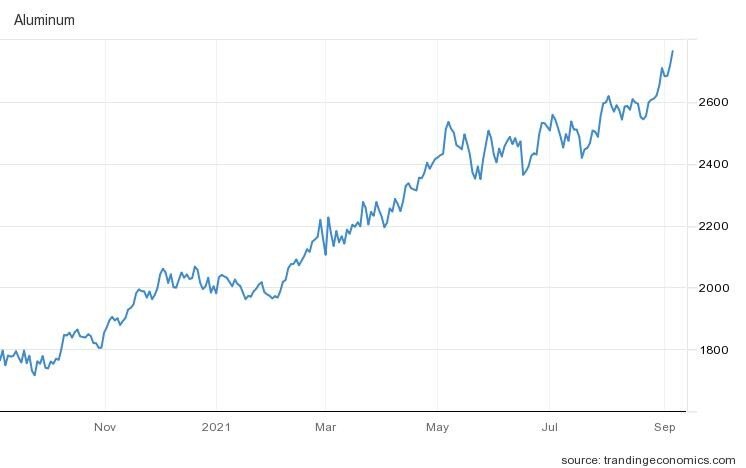

The coup d’etat in Guinea over the weekend has resulted in freight rates falling and aluminium futures rising to a ten-year high. While not the largest bauxite producer in the world, the West African nation has in only a few years become the world’s largest exporter of the commodity vital to the aluminium industry. The country’s shipments of the ore have become especially important to China, as part of its policy to reduce its reliance on imports from Australia. The bauxite produced in Guinea is also primarily destined for the export markets, as opposed to in many other prominent producers where a large portion of the output heads to the domestic aluminium industry for refinement.

Aluminium – USD per tonne

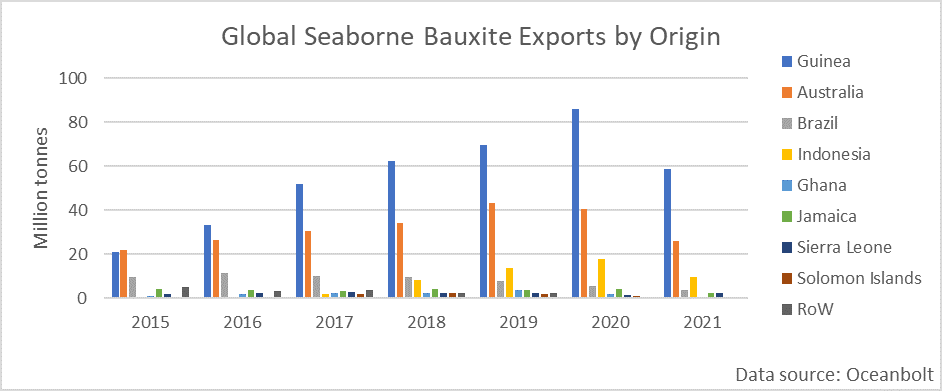

The bauxite exports of Guinea have been a real success story over the last few years, with volumes more than quadrupling between 2015 and 2020 and reaching 86 million tonnes last year. The volumes shipped so far this year have also suggested that a new record could be on the cards, with year-to-date exports at 59 million tonnes. However, the evolving situation in Guinea has the potential of derailing such a development.

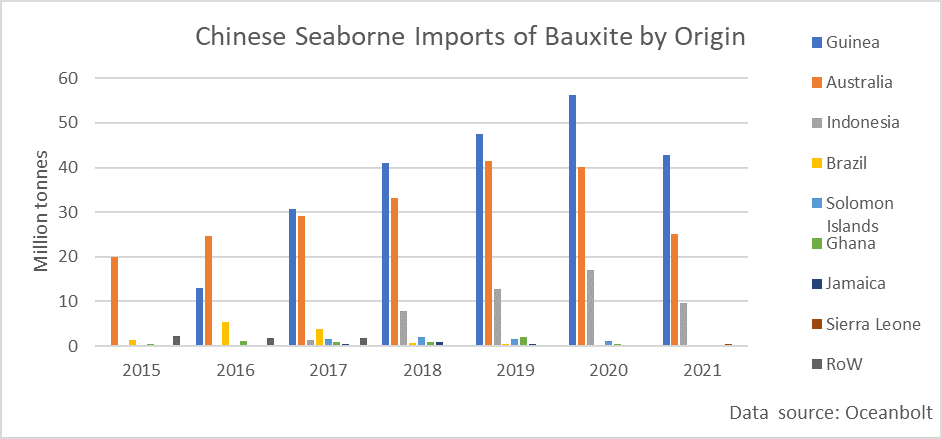

For China, the developments over the weekend in the West African nation are particularly serious and could have significant consequences, as it has rapidly become the largest supplier at the same time as the Chinese demand for imported bauxite has increased significantly. The West African nation only started to supply any substantial quantities to China in 2016 but has since dethroned Australia from the top spot. While China has a respectable domestic production at around 70 million tonnes, its demand for imported bauxite has more than doubled in the last five years. According to data from Oceanbolt, so far this year 68 per cent of last year’s record seaborne imports of 115 million tonnes has been matched, which could put the record in jeopardy. Guinea has also seen its share of the Chinese market growing further during the first eight months of the year, with volumes already at 76 per cent of last year’s volumes and a market share of 55 per cent.

It is probably difficult to exaggerate the current importance of Guinean bauxite to China, especially as the ongoing diplomatic tensions between China and Australia show no signs of abating. Earlier in the year, Guinea also expressed the ambition of phasing in an additional 24 million tonnes of annual export capacity during 2021, something that would contribute to further erosion of the Australian market share. Australia remains the world’s largest producer of the commodity, with an annual output of approximately 105 million tonnes that is projected to grow by around 20 per cent in the coming years. A move to increase imports of Australian bauxite may be unpopular with the Chinese leadership but could prove to be unavoidable if disruptions in Guinea turn out to be material and lengthy. Any new leadership is likely to recognise the importance of exports to the country’s economy, but a potential power vacuum and a threat of closed borders could generate considerable disruptions. Additionally, a new government may decide to review mining concessions and complicate Beijing’s long-term plans to source much of its bauxite and iron ore from the country to reduce the dependence on Australian imports. Under the circumstances, it is therefore easy to imagine that a new government in Guinea will be the target of extensive Chinese diplomacy.

Indonesian bauxite exports have recovered in recent years, following the law in 2014 that banned much of the exports. However, the county's total export volumes are well below what would be required to replace any large part of the Chinese imports from Guinea.

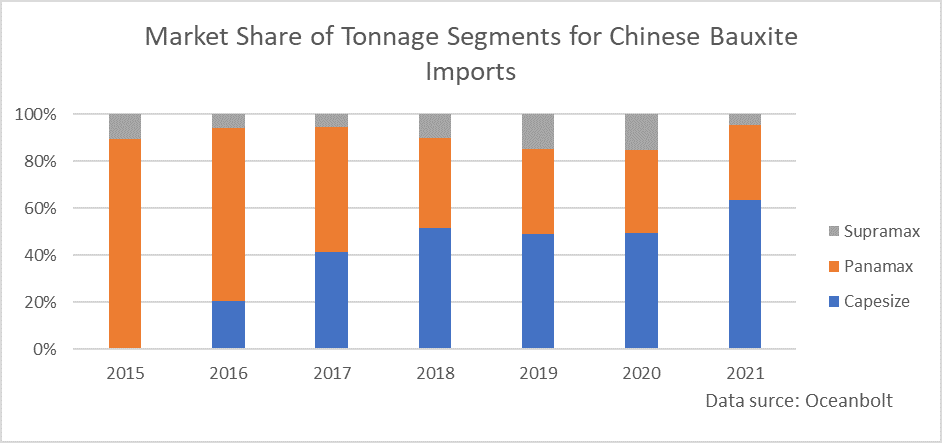

At the same time as the importance of West African bauxite has grown for the Chinese importers, the nature of the seaborne trade has also changed. From being virtually the exclusive domain of the Panamaxes in the middle of the last decade, the increasing importance of the supplies from Guinea has shifted much of the trade flow to the Capesizes. More than half of the Chinese imports are now transported by vessels in the larger tonnage segment. For the trade in the rest of the world, the shift is somewhat less pronounced but Capesizes have become the dominant segment globally as well. If Chinese purchasers are forced to scour the globe for substitutes to the West African bauxite the trend towards increasing importance for the larger tonnage could reverse, as distances and consignment sizes could shrink. Any prolonged disruptions to the exports of bauxite from Guinea are likely to be bad news for the freight rates and tonnage demand, especially in the largest segment. However, if Chinese buyers are successful in sourcing replacement volumes elsewhere, such as Indonesia and Australia, some of the tonnage demand could on the other hand shift to the Panamax segment.